Keith Fontenot, Caitlin Brandt and Mark B. McClellan

February 2, 2015 9:59am - Brookings Institution

A Primer on Medicare Physician Payment Reform and the SGR

If there is an equivalent of gGroundhog Dayh in the

legislative arena, it may be the semi-annual exercise to defer the physician

payment rate cuts called for in Medicarefs Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR)

legislation. Ever since 2003, Congress has legislated an alternative to the

automatic cuts scheduled under the law. This time, absent legislative action,

payments to physicians under Medicare will but cut by 21.2 percent starting in

April.

Last year, the three Congressional committees with

jurisdiction over Medicare came together on a bipartisan, bicameral plan to fix

the flawed system permanently. The remainder of this post explains just

what is behind this decade of gkicking the can down the road.h

For more details on how the Medicare SGR bill can be

enhanced through alternative payment models, we recommend reading,

"Medicare

Physician Payment Reform: Securing the Connection Between Value and

Payment" and Alice Rivlin's prepared

testimony to the House Committee on Energy and Commerce

Subcommittee on Health from January 21.

What is the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate?

Put in place through the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, the SGR is a system

designed to control the costs of Medicare payments for physicians. The SGR

formula was aimed at limiting the annual increase in cost per Medicare

beneficiary to the growth in the national economy. The SGR is layered on top of

a system for paying physicians known as a gphysician fee schedule,h which pays

physicians for delivering a number of individual Medicare services ("volume"),

rather than for quality or keeping people healthy ("value").

Under the SGR formula, if overall physician costs exceed target expenditures,

this triggers an across-the-board reduction in payments. The target is

based on spending growth in the economy – thatfs where the gsustainableh part of

the name comes from – but is not tied to quality or access to care. This year,

if Congress does not act by March 31, then payments to Medicare physicians would

be reduced by 21.2 percent. However, since 2002, Congress has stepped in with

short-term legislation (often referred to as the gdoc fixh) to avert the payment

reduction. These patches have kept increases in physician payments below

inflation over time, and have also resulted in a huge divergence between the

actual level of Medicare physician-related spending and the target in the SGR

formula. Consequently, the budgetary cost of permanently fixing the SGR now runs

over a hundred billion dollars. For years it has been clear that both the SGR

and physician payment system urgently need attention.

Why is the SGR such a significant problem?

Several important consequences of this outdated and

inefficient process are described below. Overall, the SGR:

Disregards individual and group performance. Because

the SGR is merely a system of budget controls it does nothing to give an

individuals or physician groups any incentives for performing more efficiently.

Regardless of how poorly or how well physicians may do on quality or efficiency

of care they are nonetheless subject to the aggregate cut.

Makes physician payments uncertain every

year. The instability caused by the threat of payment cuts is detrimental to

Medicare physicians and the program. While the formula has been

bypassed, it is difficult for clinicians to plan for the future, let

alone have the certainty they need to reform and improve care.

Distracts from other legislative priorities. Preparing

annual legislation to avoid falling off the SGR cliff chews up valuable

Congressional time. Congress has so little time and so much else to do that an

annual SGR patch diverts attention from other important issues including

implementing better payment models.

Defers program improvements. The high cost of permanent

repeal – in the range of $150 billion over ten years -- has effectively locked

us in to a pattern of annual extensions that has thus far stymied Congressional

reform efforts.

Presents a threat to health of seniors. Although surveys

have not shown significant deterioration in beneficiary access at the national

level, the standard for payment in Medicare should not be whether or not

problems of access to care have reached a substantial level.

How did we get in this mess?

It is important to remember that the SGR was an attempt by

Congress to address a very real problem: the underlying physician payment

system pays physicians for providing more, not better care.

Previous efforts at controlling the cost of physician spending in Medicare

had proven ineffective and so in 1997 Congress adopted the SGR formula.

Recall that the formula ties physician payments to growth in

the national economy. In the late 90s, while economic growth was high and

medical cost growth was low, the system produced increases in physician payments

and no cuts were necessary. In 2001, however, the combination of a

recession (declining GDP) and increasing medical costs led to an automatic cut

of 4.8 percent in 2002, and each year thereafter.

This also exacerbated the problem because of the

cumulative nature of the SGR. To minimize the budgetary impact of the gdoc fixh,

Congress actually increased the reduction in succeeding years to make up

for the cost of the fix in the current year. For example, if the formula called

for two years of five percent cuts, Congress instead legislated one year of no

cut and one year of a ten percent cut. This approach has led to the looming 21.2

percent cut.

Why does SGR cost so much?

Under current law, physician payments are scheduled to be

reduced. Measured against that gbaselineh of spending, the legislative action to

maintain current payments does score as a cost. However, Congress also

operates under a requirement to pay for the costs of new legislation so most SGR

extensions have included adjustments to other health related payments, such as

an extension of the Medicare sequester. So in that sense, the SGR has functioned

to create pressure to hold down costs, just not in the way the SGR formula

intended.

Moreover, the need to offset spending has led to a squeeze on

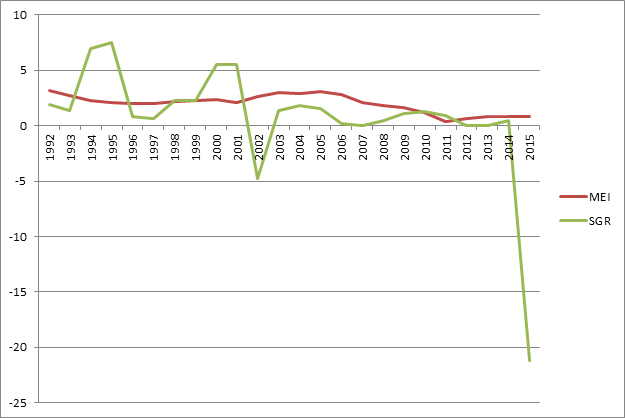

physician payment rates over the past dozen or so years. Figure 1 below

compares the Medicare Economic Index (MEI), a measure of physician practice cost

inflation, to the actual SGR updates from 1992 through the scheduled 2015

changes. At points in the past the annual updates for physician payments

greatly exceeded the MEI, but since about 2001, they have generally been below

the MEI. So while the formula has not operated as it was designed since 2002 it

has placed significant limits on increases in reimbursement for physician

services.

Figure 1. Medicare Economic

Index and Sustainable Growth Rate Comparison

How can we permanently fix this flawed system?

The most important thing we can do to continue to push health

reform forward is to move away from our current gfee for serviceh system.

Instead, we must transition to payment models that involve greater

accountability for providers for the quality and cost of the care they deliver.

A more effective payment system would recognize that physician decisions have

significant impacts on overall health care costs, and better

support physicians to make improvements in the delivery of care. In

addition, many services that physicians provide – from responding to emails, to

helping patients develop care plans– are not supported by the current

fee-for-service payment system. Last year's tri-committee bill

was developed around a proposal to replace the SGR with a new system that

supported galternative payment modelsh, such as Accountable Care Organizations

(ACOs), bundled payments and patient-centered medical homes. Though it

could be improved, this legislation is a good start. For more information on the

implementation of alternative payment models, read our Medicare

reform health policy brief.

What is the potential for actually getting something done?

This is a huge challenge. The cost of last yearfs legislation

is in the range of $150 billion over ten years. And unfortunately there

has been virtually no discussion of how to pay for it. Elsewhere, we wrote

about how

to pay for a permanent SGR fix, and suggested that if such a discussion

proves to be too challenging, then Congress should consider a semi-permanent fix

in the three to five year range. It is critical that physicians have a

period of stability and incentives to invest in the management tools that will

help them move away from the current, inefficient, fee for service models.

With a new Congress it remains to be seen how this will

proceed. There are new Chairmen in two of the major committees – House Ways

and Means and Senate Finance. While they support reforming the SGR system it is

possible that they will want to review last yearfs legislation and consider

changes. With the current gpatchh expiring in March, some action will have

to be taken quickly to avoid precipitous payment cuts. Because there

is little time before then to develop consensus around the legislation and how

to pay for it, the odds again favor some sort of further short term extension.

But this could be done in a way that facilitates a permanent or semi-permanent

fix soon, perhaps in this Congress. If Congress, adopts a new budget and moves

to implement it, it is quite possible SGR will be included as one of those

items. That process, however, can take several months to unfold.

Keith Fontenot

Visiting Scholar, Economic

Studies, Engelberg

Center for Health Care Reform

Keith Fontenot is a visiting scholar in the

Engelberg Center for Health Reform, under the Economic Studies program at the

Brookings Institution. Mr. Fontenot is veteran of budget, legislative and

analytical issues surrounding the nation's health and other major entitlement

programs.

Caitlin Brandt

Research Analyst, Economic

Studies, Engelberg

Center for Health Care Reform

Mark B. McClellan

Director, Health Care Innovation and Value Initiative

Senior Fellow, Economic

Studies

Mark McClellan, MD, PhD, is a senior fellow and director of the Health Care

Innovation and Value Initiative at the Brookings Institution. Within

Brookings, his work focuses on promoting quality and value in patient centered

health care. A doctor and economist by training, he also has a highly

distinguished record in public service and in academic research. Dr. McClellan

is a former administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

(CMS) and former commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA),

where he developed and implemented major reforms in health policy. These

include the Medicare prescription drug benefit, the FDAfs Critical Path

Initiative, and public-private initiatives to develop better information on

the quality and cost of care. Dr. McClellan chairs the FDAfs Reagan-Udall

Foundation, is co-chair of the Quality Alliance Steering Committee, sits on

the National Quality Forumfs Board of Directors, is a member of the Institute

of Medicine, and is a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic

Research. He previously served as a member of the Presidentfs Council of

Economic Advisers and senior director for health care policy at the White

House, and was an associate professor of economics and medicine at Stanford

University.